Bookshop links are affiliate links. Also, standard disclaimer that I’m not going to be logged on much today!

The Best of Nancy Kress (Nancy Kress, 2015)

The first story in this collection, “And Wild For to Hold,” was so good I immediately paused any further reading to go text friends about it. One said (paraphrased), “Nancy Kress is talented, but sort of evil.” Further discussion made it clear my friend was talking about the novel Beggars in Spain, and the original novella of that story is the final piece in this volume, so as I continued to read The Best of Nancy Kress I felt what I can only call a sense of Doom every moment I got closer to “Beggars in Spain.”

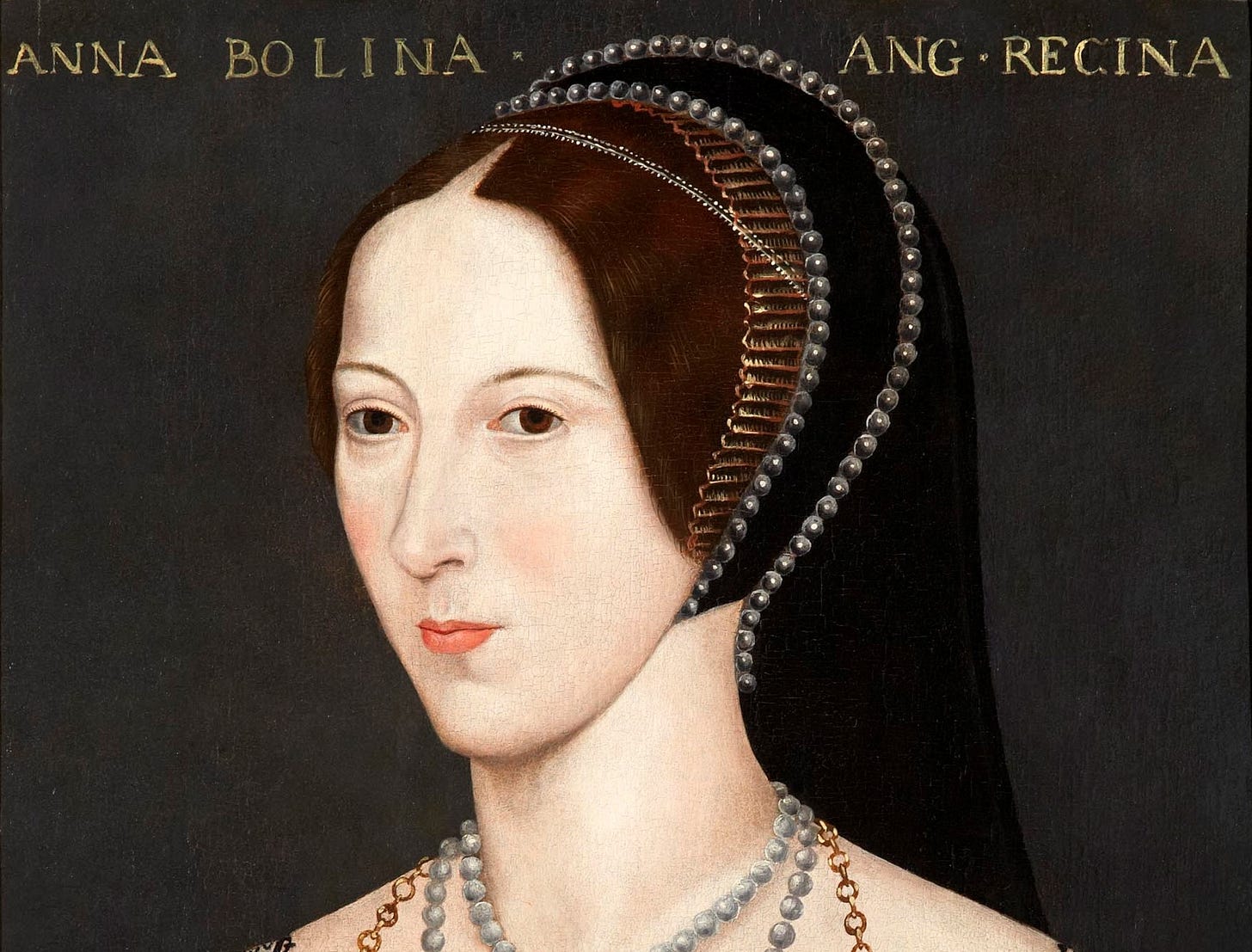

But to return for a moment to “And Wild For to Hold”—this story is about an organization which extracts people from the past they’ve deemed crucial pivot points in history. By removing these people, they avert war and bloodshed. These “holy hostages” include Helen of Troy, Adolph Hitler, the Tsarevich, and, now, Anne Boleyn. But A…