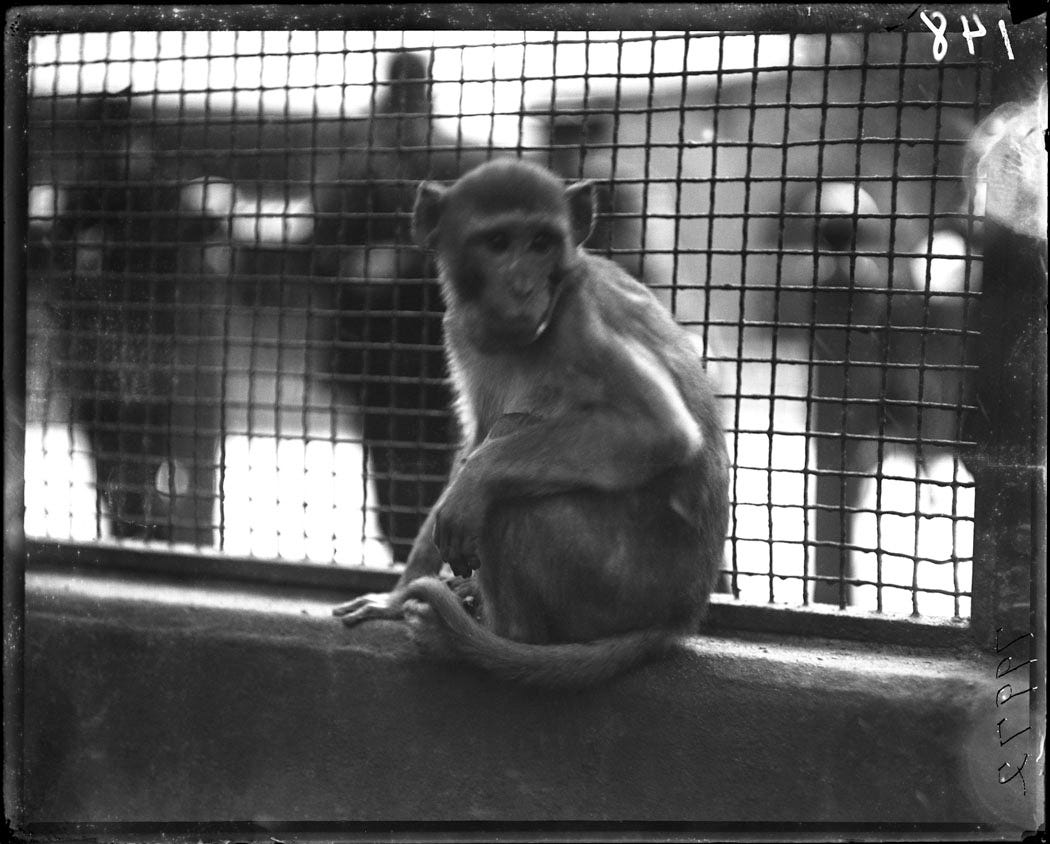

At The Point, my third essay talking about “genre” short stories is out. (Previously: C.L. Moore, Fritz Leiber.) This time it’s “Mother of Cloth, Heart of Clock,” by Craig Strete, a story written from the perspective of a doomed lab animal:

The most widespread and ancient relationship between humans and the other animals, though, is the rejection of identification. The animal is no longer our neighbor in a shared world but a substance: meat to eat, skin to wear—and, more recently, a tool for scientific investigation. We may ask ourselves how the animals feel about it, or try to minimize their suffering, but our knowledge that they aren’t fans and would prefer not to be treated this way doesn’t really affect our decision to continue experimenting on them. It’s not as if we think they’re enjoying themselves. We’re animals too, after all, and we can tell. As the narrator of Craig Strete’s story “Mother of Cloth, Heart of Clock” comments: “I care about them going to kill me. Wouldn’t anyone? Ask anybody else in these cages and they’ll all tell you the same thing. Nobody likes to get killed.”

Read it here.

There are naturally a lot of stories about the animal perspective that are left out of this essay (Black Beauty, Call of the Wild, Bambi, The Peregrine, etc), some of which I’ve read and some of which I haven’t. I owe reading Olaf Stapledon’s Sirius to William Emmons (thanks to this review he wrote) and I owe reading Clifford Simak’s City (read, but not mentioned) to this person on Reddit. (Is this person one of you?) I’m so-so on City but Sirius is great. Don’t take my word for it, take this other person’s word for it.

A book I read after I filed was Oliver Soden’s Jeoffry: The Poet’s Cat. I found that book to be at its best when it was not trying to be a biography of Jeoffry, but it had some lovely moments and it’s not very long, so if you’re curious it’s worth a look.

The genre story that I think is most interesting to read alongside “Mother of Cloth, Heart of Clock” is James Tiptree’s “The Psychologist Who Wouldn’t Do Awful Things to Rats.”1 (It seems possible to me that Tiptree and Strete, who were friends, corresponded about animal experimentation at some point, but that’s just a guess and not based in anything I’ve read.) Tiptree’s story came out a year later and draws on the real Alice Sheldon’s experience doing research on rats. The story is not an attempt to understand rats, but it is about answering the question of if there might be a way to learn things from rats that don’t involve torturing them.2

I mention in the piece that Strete’s career was derailed by an accusation of plagiarism that was probably not true. You may be wondering what that means. I wrote a bit about it that didn’t fit in the piece, but for the nosy, I’m putting the details in here. Essentially, Strete was accused of taking the entire novel of a writer named Ron Montana and publishing it as his own.

To be honest, if I’d realized when I picked this story that Craig Strete’s biography was so beset with questions and controversy, I almost definitely would have picked a different story by a different person, just to make things easier on myself. But since I’d announced the four stories in advance I couldn’t be a lazy coward about it. There’s a single box of Strete’s “papers” at Bowling Green. I looked into it, a phrase which I mean in the most literal sense possible: I opened the box and looked into it. Investigations ceased there as it doesn’t contain much, and what it contains is mostly books. So while I was hoping I’d find, you know, a letter from Salvador Dalí in there, I did not.

Let’s go now to.…

…The Cutting Room Floor

In one extended treatment of this incident, a reminiscence from Sheldon Teitelbaum, a science fiction critic, this plagiarism seems to have been an unfortunate but honest mistake:

The story floating about was that Montana had labored over a novel, and then awoke one day to discover it had been printed under a stranger’s name, notably Craig Strete. No mention, of course, that Strete and Montana had collaborated on the novel. Or that, upon parting ways, the two had agreed to take their respective contributions and develop them on their own for individual publication. No mention either that the publisher—this in a conversation with me—had received the wrong manuscript from Strete, and then failed to substitute it with the correct one when Strete informed him of the switch.

Strete, however, had attracted a powerful enemy (according to Teitelbaum), one who was happy to exploit what could have been an easily repaired error. That enemy’s name was Harlan Ellison—a writer and editor who was brilliant, unstable, vengeful, loyal, litigious, and paranoid in equal measure. He had wanted Strete for a planned anthology, Last Dangerous Visions, a sequel to Ellison’s two blockbuster anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions. Strete had initially agreed, but then withdrew the story. For this withdrawal, Teitelbaum believed, he attracted Ellison’s undying wrath, and Ellison set about systematically destroying Strete’s career once granted the opportunity.

What to believe here? Teitelbaum, who hated Ellison, had his own axes to grind (he is strangely fixated throughout his recounting of these events on Ellison’s lack of support for the state of Israel, something which does not seem to bear on the situation at hand), but nothing about it is implausible. Ellison was litigious and petty. People were afraid of him. Last Dangerous Visions is one of the few books that can be described as suffering from “production hell” the way movies are said to do. In 1987, Christopher Priest, one of several writers who had once submitted a story for Last Dangerous Visions, pointed out the anthology had been presented as on the verge of coming out since 1972 and that if everything Ellison claimed about it was true, it would have been 5,000 pages long. Priest continued to update his pamphlet on the situation, which he called “The Last Deadloss Visions,” and the 1994 version lists twenty-four authors whose stories were supposedly included but who had died in the meantime. Ellison himself died in 2018 without seeing Last Dangerous Visions into publication.

Personally? I believe the Teitelbaum version of this story.

Much thanks as always to Becca Rothfeld and Julia Aizuss for their work on this piece!

Another excellent essay -- thanks!

I have to acknowledge that I am sufficiently plugged into science fiction (and sufficiently old!) that I HAVE heard of Craig Strete. I was subscribing to Galaxy back then, and I read Sturgeon's review, and in fact Street published stories in Galaxy -- "The Bleeding Man", "Horse of a Different Technicolor" -- and "Time Deer" was reprinted in the last issue of Galaxy's sister magazine If. I also remember the controversy about plagiarism, and that he was cleared (in the minds of most people) of that charge -- and it was a shame that after that you really didn't see his stories any more.

I also overestimated how many people had heard of him when I wrote a quiz about science fiction by people of color a couple of years ago. I put in a question about Strete, and I think only 2 people, out of several hundred that too the quiz, got it right -- which was NOT my intention at all, but certainly supports your suggestion that few people will have heard of him!

enjoyed this! had been anticipating it, and had my anticipation rewarded. i suppose there is less of a plot to talk about than the previous two stories, but that makes sense as the protagonist is not rly capable of grasping what a plot is

animal perceptions in literature...i liked Diana Wynne Jones' Dogsbody, where an enormously powerful (but also, as the title indicates, slightly harassed) alien is incarnated as a young girl's pet. i think some people didn't like the combination of girl-and-her-dog sentiment with a rather busy science-fiction frame, but surely if dogs could tell stories, they would prefer them sentimental and rich with incident...but i really read it too long ago to be theorizing. Tiptree herself, in Love Is The Plan and iirc some sections of Up The Walls Of The World. (the hero of Love Is The Plan is not really an animal but they are resigned to their fate in the way you describe in the piece, as indicated even by the title.) i never really find that the talking animals/werewolves/etc in Discworld are "realistic animals" so much as "realistic to how animals would be in a Terry Pratchett novel." last and imo greatest, Danny Lavery's piece about being the goose from that one videogame