The Story Until Now (Kit Reed, 2013)

Bookshop links are affiliate links the government makes me put this in every time I still haven’t actually set up any way to get the money out of my affiliate account because frankly there’s like $18 in there. I don’t blame you however I always look for cheaper options too we’re all broke here at BDM Industries and its Allies.

A true fact about 60s and 70s women’s science fiction is that there is really too much to write about. Every time I pick up something to read as background I’m confronted by some wonderful weirdo that feels as if she surely deserves a book of her own. On the other hand, it strikes me as prudent not to write too much about the authors who will be focuses of the book on here. So the abundance of weirdos is a blessing: there is lots to write about even if I avoid directly touching on my main girls very often.

Carol Emshwiller is one of these writers who doesn’t feature as a main player but deserves to; however, I plan to review her forthcoming selected short stories, Moon Songs, so we’ll put a pin in her1 for now. Another one, a recent discovery, is Josephine Saxton, who is British and thus ineligible for inclusion in the book anyway, but her novella The Travails of Jane Saint is a very funny trip through dreamworld2 that involves a courageous dachshund named Merleau-Ponty.3

But the one I want to talk about in this post is Kit Reed. Reed published her first story, “The Wait,” in 1958, and she published her last story the year she died, in 2017. In between she published, if not literally countless stories, at least more stories than I want to count.4 Also, I am going to experiment here with a new post format, in which there is a complete “capsule review” as it were of The Story Until Now, then a paywall, behind which will lie some discussion of a specific Kit Reed story, “Songs of War,” her version of a “battle of the sexes” story. As I say, this is an experiment.

I mentioned Emshwiller and Saxton earlier because Emshwiller, Saxton, and Reed all feel like they fit into a lineage whose most prominent figure these days is Kelly Link.5 They tell stories that project a strong feeling of normality but the gap between what the story presents as “normal” or the narrator considers “normal” and what we do is not only massive but unpredictable; it seems essential to the ways these stories work (at least as a body of work) that every once in a while what is common sense in story world is the same as what is common sense in our own.

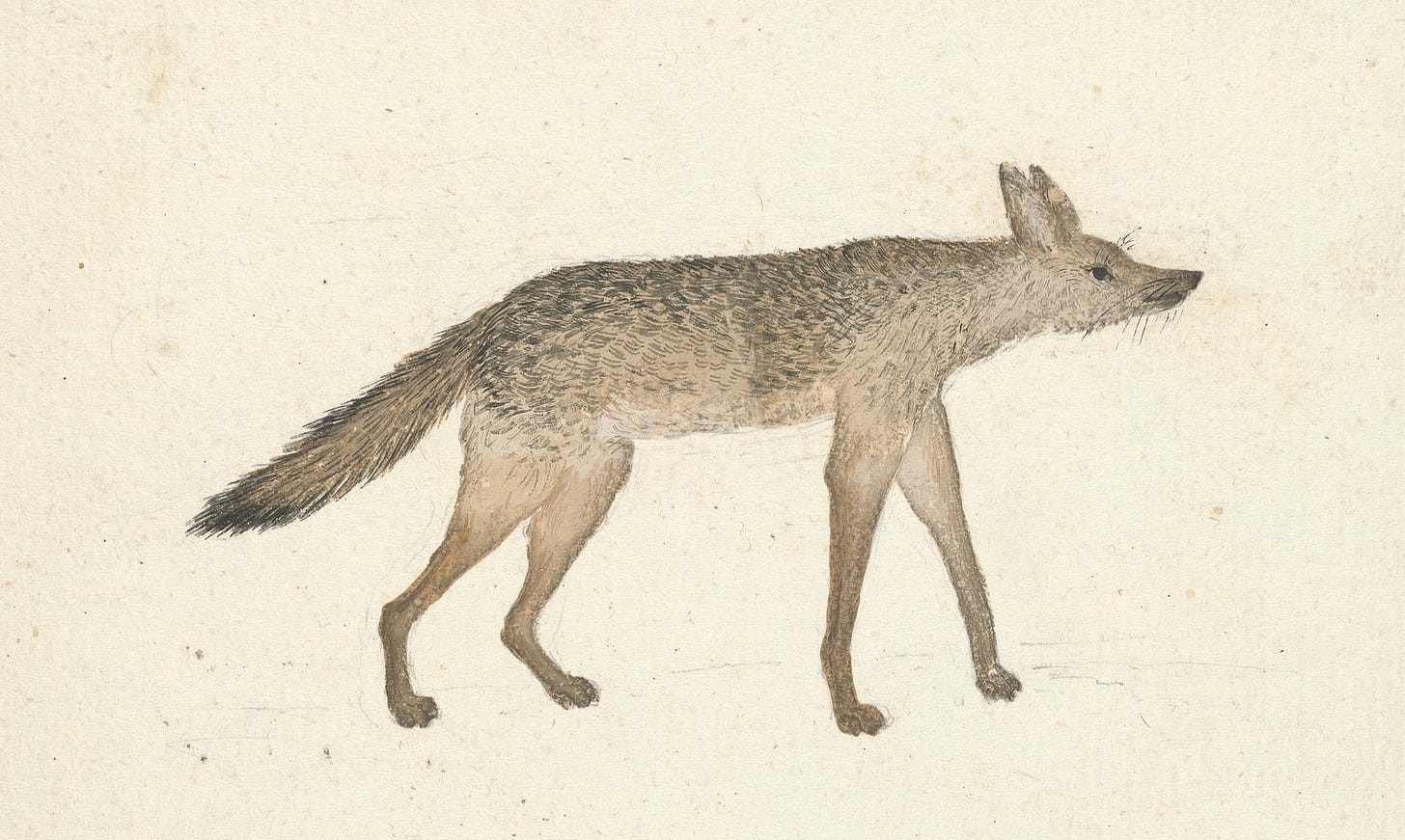

To this technique, Kit Reed often adds a twist of her own: stories about people who are abruptly switching from one “normal world” with one set of priorities to a different “normal world” with a different set of priorities. In “What Wolves Know,” a boy who has been raised by wolves is returned to the bosom of his ambiguously loving family (“the wolves aren’t Happy’s real parents. In a way this is news to him, but from the beginning he had suspicions”). Which world deserves one’s allegiance? Which set of values should you try to maintain? Is choosing between them even possible?

In another story, an inverted version of “The Metamorphosis,” Joseph Bug, a cockroach, awakes to discover he’s turned into a human being. Rejected by his old friends, he begins to smash them: “I had for the first time power, and as I thought on the injuries the others had done me, this new power tasted sweet.” Glorying in his newfound superiority over his onetime peers, he proclaims to the other cockroaches: “Now I understand. The lesser will always hate the great.” In the end, however, Joseph Bug doesn’t fare much better than Gregor Samsa.

That both of these worlds are often crazy is part of the charm. Mismatched but equally bizarre normalities are used to great comic effect in “High Rise High,” where a city has put all of the teenagers in a giant impregnable high-rise fortress, only for the teenagers to revolt and take over. Agent Betsy, who is actually thirty-five but who can pass for a teen, is sent in to infiltrate the guerilla leadership. In her teenage persona as “Trinket” she instantly gets swept up in the emotional high school world she never got to have as a real teenager:

Onstage with Johnny, cute, popular little Trinket is so caught up in the moment that she forgets who she used to be. The crowd roars and that stringy, unhappy, capable person whose dad died in the line of duty which is why she’s such a good cop fades away. She fingers the silver Scrunchy Johnny put on her wrist excitedly because she’s about to get everything she wants! In her life outside HRH, Betsy Gallaher went to her high school junior prom alone and her senior prom with a blind date who threw up on her feet, and no matter how smart a woman is, or how accomplished, no matter how smart you are, hurts incurred in high school never go away; they just go on hurting. Well, life’s unexpectedly turned around for her. Trinket is going to the Tinsel Prom at HRH with the hottest boy in the entire school.

Now, as Agent Betsy, our heroine not only knows the situation in HRH needs to be shut down but that the town (however improbably) has a nuclear arsenal and is going to nuke the high school if she can’t fix things. But as Trinket…? In fact, though, while the situation in “High Rise High” is ultimately resolved without nuking the school, Agent Betsy / Trinket herself has little to do with it.

With Sayaka Murata we talked a bit about normalcy—Normalness Studies?—and I think one thing you find in these Kit Reed stories is a similar interest in the way there is something a bit unnerving about the plastic nature of the normal. People have the wrong priorities, such that they cannot be reasoned with; people are either too easily changed by changes in circumstances or too rigid to change at all (or a freakish combination of the two, as is the case in “The Wait”). Reed very much exploits the fact that her readers will already be primed to find new and strange worlds in her stories; there’s a constant negotiation at play among what you expect, what you get, and what you can assume.…

Behind the paywall: Some discussion of “Songs of War.”